Let’s go back to where this started…

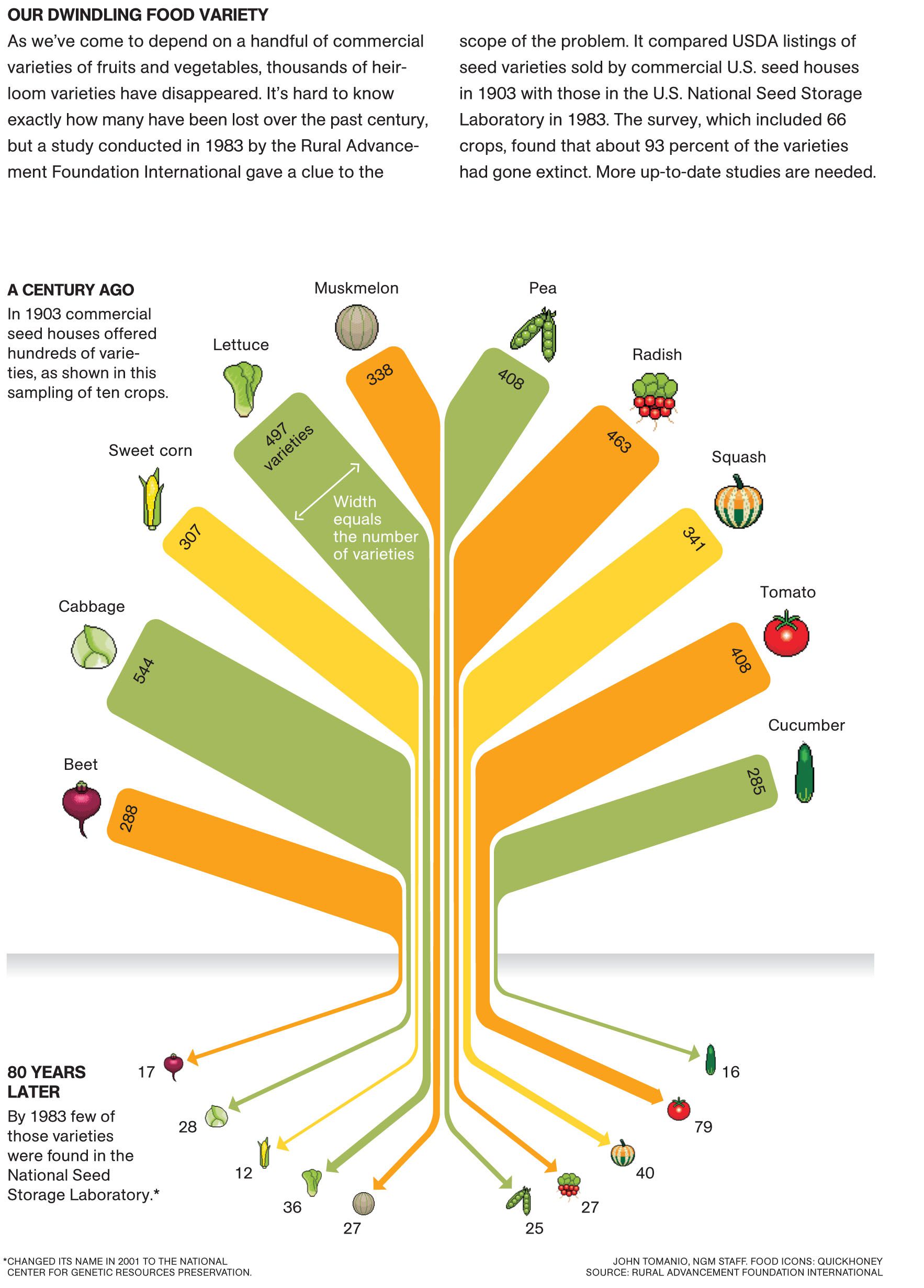

Let’s start this post where the story began for me. We’re going to reach back into the old stack of National Geographic magazines, looking for an issue back in July 2011. John Tomanio put together an infographic that rocked me to the core.

Why does that image matter so much?

- You are getting a lot less visual diversity on your plate, fewer colours, textures, and tastes. In short: your food doesn’t need to be this boring. Thousands of choices have been taken away from you;

- You are getting a narrower range of nutrients into your body, because the handful of species being produced in bulk today were selected for their productivity (in volume) and their ease of transport… not how good they are for you, for the land that they are grown in, or for the people growing them;

- You are losing your connection to your culture’s richness, because 10,000 years of farmers before you have been selecting specific plants for their diet based on what was endemic to the area, what could be coaxed to grow, and then shaping that selection over thousands of years to produce foodstuffs that helped make you who you are today;

- You are ingesting food that was designed to work with an industrial food complex, right down to the inclusion of new genes so that those plants wouldn’t be killed by swimming in pesticides;

- You are ingesting food that was designed to be more profitable to a very small handful of companies, and unless you hold stock in them, that money is not benefiting the farmers, their families, their communities, or even necessarily a company with a head office in your country; and

- You are supporting (via your purchases) the decision to limit our foodstock to a terrifyingly narrow range of plants. As climate change accelerates, you have bet your future that:

- Changes to temperatures, wind, sun, cloud cover, precipitation, and the seasonal cycles for each will not cause this dreadfully short list of crops to fail; and

- The indirect impacts of those changes such as changes to the soil microbes, diseases, insects, and animals in farming areas will not cause that dreadfully short list of crops to fail.

How did we get here?

Over the last ten thousand or so years of agriculture, seeds have been bred and shared openly between farmers, communities and governments. The people planting those seeds select many related varieties of the same plant each year, and kept seeds of varieties that they weren’t planting. Why? Each year, some did better than others, and even the best farmer couldn’t predict all possibilities that would impact they crop. Farmers had a close and personal relationship with their seeds, and deep experiential knowledge about how each variety performs under varying conditions.After World War Two, there was a major shift in thinking around farming. There was a transition from open-pollinated to hybrid seed. With the task of feeding a growing population, agricultural scientists bred crops for yield, nitrogen uptake efficiency, pesticide resistance and shelf life. Hybrid seed became increasingly productive and widely available. With hybrid seed, farmers could choose more productive varieties that required less labour. A decreased demand for labour facilitated urbanization throughout the 20th century, which also meant a general loss of knowledge of how to farm, as people moved out of rural areas. Access to hybrid seed as well as declining numbers of farmers also led to a loss of seed saving expertise, and since the green revolution 75% of agricultural biodiversity on earth has been lost. Reclaiming biodiversity is thus a critical goal of the food sovereignty movement.

If you think that these claims are exaggerations, I would like to point at The Great Famine of Ireland. Nearly a million people starved when their preferred foodstock (a single variety of potato) turned out to be vulnerable to blight. Since everyone had the same thing planted, there was no fallback position. It’s why the O section of the Boston phonebook is the longest section.

- Focuses on food for people. Food is more than a commodity. People’s need for—and right to—food must be at the centre of policies.

- Builds knowledge and skills. We need to build on traditional knowledge, using research to support this knowledge and pass it to future generations. We also need to reject technologies that undermine or contaminate local food systems.

- Works with nature. We need to optimize the contribution of ecosystems and improve resilience through the use of diverse agroecological production and harvesting methods that and improve ecosystem resilience and adaptation, especially in the face of climate change.

- Values food providers. We need to support sustainable livelihoods for farmers and everyone else involved in food production or harvesting, and we need to respect their work.

- Localizes food systems. We need to reduce the distance between food providers and consumers, to reject dumping and inappropriate food aid, and resist dependency on remote and unaccountable corporations for food and seed.

- Puts control locally. We need to place control over food systems in the hands of local food providers and reject the privatization of natural resources. We also need to recognize the need to inhabit and share territories.

- Food is sacred. Food is a gift of life, not to be squandered. It cannot be commodified.

Want to learn more?

Below are a selection of movies on this topic. They do a much better job than I do explaining how we got here, and what we need to change to protect our food supply.

[This is a brand-new movie, unlike the links that follow. Sorry, you’d have to buy it to watch it!]

Based on events from a 1998 lawsuit, Percy follows small-town farmer Percy Schmeiser, who challenges a major conglomerate when the company’s genetically modified (GMO) canola is discovered in the 70-year-old farmer’s crops. As he speaks out against the company’s business practices, he realizes he is representing thousands of other disenfranchised farmers around the world fighting the same battle. Suddenly, he becomes an unsuspecting folk hero in a desperate war to protect farmers’ rights and the world’s food supply against what they see as corporate greed.

Percy Schmeiser died on October 13th 2020, 4 days after the film’s theatrical release. He was 89 years old.

“The reality is that in spite of the unrelenting pressures they face, it is these farms who feed seventy percent of the world’s population. These traditional farming systems use less land, less water, and fewer resources. They grow healthy, nutritional food, and nurture greater crop diversity. They protect soils, water, and ecosystems, and they are proving more resilient in the face of climate change. It is these farming methods that can show us the way forward for real food security.”

sov.er.eign.ty (food)Noun

Seeds of Justice – In The Hands of Farmers (2015), narrated by Jon Snow, is the third film in the trilogy. It follows Ethiopian plant geneticist Dr Melaku Worede’s inspirational work to re-valorise farmers’ knowledge and protect their position as guardians of seed diversity. Treading in Melaku’s footsteps from his youth to the present day through his pivotal experience of Ethiopia’s infamous famine, the film questions one of society’s most flawed assumptions: that scientists hold the answers to ending hunger, not farmers. Even within a single crop in Ethiopia, the level of genetic diversity is astounding.

Drought in Ethiopia 1983 to 1985 caused foreign aid to pour into the country, but efforts refused to recognize local conditions. They tried to eliminate teff, replacing it with corn, and the situation only got worse. Dr. Melaku Worede turned everyone’s assumptions about gene banks on their head, creating a distributed set of seed stores based in the community, for the use of the community. Their local knowledge was the key to selecting the right seed variety for their unique conditions, as microclimates could produce radically different growing conditions in as short a distance as 5 kilometres. While his indigenous seed work with farmers was seen as anti-science by some people, it was based on empirical evidence gathered by the people growing and eating those crops.

What can I do?

- Get involved in policy-making. Policies have far-reaching impacts on our food, our health and farmers’ lives. Defend farmers’ rights and seed change. Currently, in Canada, the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act contains a provision called “farmers’ privilege” which allows farmers to save seed of protected varieties for their own use, provided they do not sell that seed. Now, the Government of Canada is considering restricting and/or removing the farmers’ privilege.

- When buying food, buy from local farmers where possible.

- When buying garden seeds, buy open-pollinated varieties. Organisations such as Seed Savers Exchange, Native Seeds/SEARCH and many others have worked for decades to maintain seed diversity and to make heirloom varieties accessible to the public.

- Learn to save seeds. The organisations listed above frequently host webinars and provide online guides.

- Re-zone your neighbourhood to allow community gardens where seeds and seed education can be shared.

- Share seeds, along with their stories – seeds can connect us to our family histories, neighbours, and landscapes. These connections facilitate understanding as well as conservation.

- Start or join a seed library.